children lose their natural resistance to

illness by habituating so closely in the residential

schools and that they die at a much higher rate than in

their villages.

But this does not justify a change in the policy of this

Department which is geared towards a Final Solution

of our Indian Problem.”

as a matter of fact, that this country ought to continually

protect a class of people who are able to stand alone.

That is my whole point. Our object is to continue until

there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been

absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian

question, and no Indian department, that is the whole

object of this Bill” (D. C. Scott, 1920)

TRC Calls to Action

As mentioned on the front page, teaching can be a wonderful and frightening act. It can help people enrich their lives, better themselves, and broaden the scope of their humanity. It can also be a means of destroying a way of thinking, for repressing a culture or ideas and it can used subjugate an entire group of people.

Before I go further, I would like to state that I’m assuming the readers of this blog have a general understanding of Residential Schools and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. For those that would like more information, please check out the following two links for more information.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

National Center for Truth and Reconciliation

If we are address the dangers of teaching it would be beneficial to look at it from the perspective e of those that have been done by harm by. I would argue that, for the most part, non-native children here in Canada have a rather positive or at least benign experience with school. By seeing it through the eyes of those that suffered because of others’ teaching practice we may have a better appreciation of how to be better teachers by being more aware of potential negative consequences.

The truth and reconciliation commission published a list of 94 Calls to Action in 2015 based on thousands of testimonies and affidavits presented by survivors and children survivors of residential schools.

It begins by stating:

“In order to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission makes the following calls to action.”

The 94 calls to action are a vital document that Canadians should be at least familiar with, if not have read in some capacity.

For the sake of this Entry I will focus on the ones that pertain to the nature of teaching and education. I won’t talk about all of them at great length but I will try to do justice to the ones I mention.

- We call upon all levels of government to fully implement Jordan’s Principle.

Named for Jordan River Anderson, this call to action states that when there is a dispute about jurisdiction and obligation of payment for services for status children, the point of first contact is to pay and to have disputes settled later. This is to avoid unnecessary delays that might lead to the harm of a child, student or patient.

- We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to develop culturally appropriate parenting programs for Aboriginal families.

In our course we talk a lot about teaching as transmission of knowledge but what if the knowledge that was to be transmitted was lost due to a program of deliberate destruction?

- We call upon the Government of Canada to repeal Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

The SPANKING law. The law, basically protects teachers, parents or others acting in such authority from criminal prosecution for using force upon a child. Considering what FNMI students went through, in terms of abuse, this call for a repeal is quite understandable.

The following calls to action are related to the funding of education to address reconciliation. This is an area where I need to do more research so for now, I encourage you to read them and become familiar with them. As time, and my blog progresses I hope to have greater insights in to this area.

- We call upon the federal government to eliminate the discrepancy in federal education funding for First Nations children being educated on reserves and those First Nations children being educated off reserves.

- We call upon the federal government to prepare and publish annual reports comparing funding for the education of First Nations children on and off reserves, as well as educational and income attainments of Aboriginal peoples in Canada compared with nonAboriginal people.

- We call on the federal government to draft new Aboriginal education legislation with the full participation and informed consent of Aboriginal peoples. The new legislation would include a commitment to sufficient funding and would incorporate the following principles:

- Providing sufficient funding to close identified educational achievement gaps within one generation.

- Improving education attainment levels and success rates.

iii. Developing culturally appropriate curricula.

- Protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, including the teaching of Aboriginal languages as credit courses.

- Enabling parental and community responsibility, control, and accountability, similar to what parents enjoy in public school systems.

- Enabling parents to fully participate in the education of their children.

vii. Respecting and honouring Treaty relationships.

- We call upon the federal government to provide adequate funding to end the backlog of First Nations students seeking a post-secondary education.

This is one of those fun ones for me because I have SO many people in my life that say things like, “gah, these indians get free university, why can’t they be successful.” This is the Disneyfied© version of what I’ve heard. I have little doubt that you’ve heard worse or have thought something similar. This sentiment is one of those warped misconceptions that only proliferates racism and hatred. FNMI people don’t get “free university.” They need to apply for funding from their band like most other students apply for scholarships. If the band has no funds or chooses to place their money into other programs then those students may be out of luck. (Murray, 2012)

- We call upon the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, in consultation and collaboration with Survivors, Aboriginal peoples, and educators, to:

- Make age-appropriate curriculum on residential schools, Treaties, and Aboriginal peoples’ historical and contemporary contributions to Canada a mandatory education requirement for Kindergarten to Grade Twelve students.

Age-appropriate here is the key. I’ve heard many teachers say that the subject is too hard to discuss with young children. But how young is too young? We are not talking about being graphic here or sexual education. Kindergarten? Perhaps too young? Grade 6… to late?

- Provide the necessary funding to post-secondary institutions to educate teachers on how to integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms.

This should also include school boards, not just post-secondary institutions, in my humble opinion.

iii. Provide the necessary funding to Aboriginal schools to utilize Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods in classrooms.

- Establish senior-level positions in government at the assistant deputy minister level or higher dedicated to Aboriginal content in education.

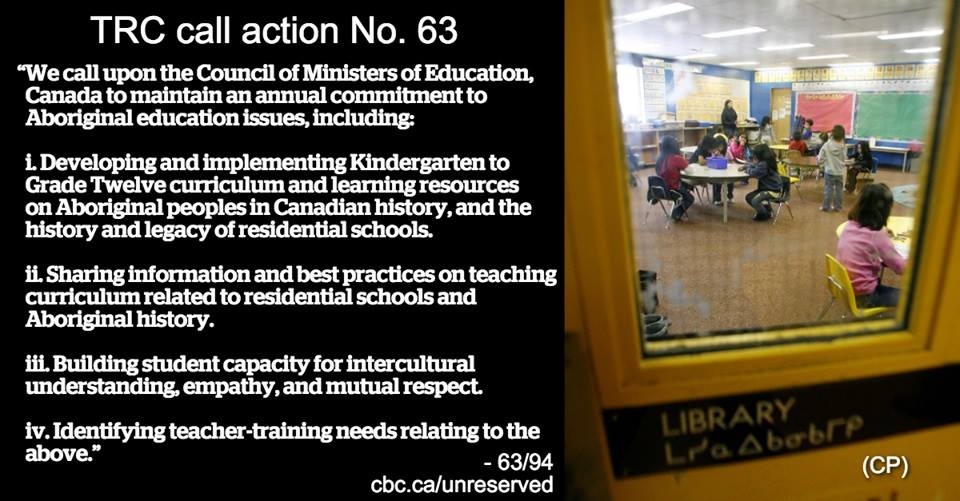

- We call upon the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Aboriginal education issues, including:

- Developing and implementing Kindergarten to Grade Twelve curriculum and learning resources on Aboriginal peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools.

- Sharing information and best practices on teaching curriculum related to residential schools and Aboriginal history.

iii. Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect.

- Identifying teacher-training needs relating to the above.

Of all the calls to actions, this one, 63, speaks to me most in terms of impact and immediacy. Most likey because I am a teacher. If there is any way for me to enact or help bring about change and reconciliation, it is through this particular Call to Action.

There are others, such as creating Early Childhood Education programs, offering degrees in aboriginal languages (12 and 16 respectively) and many others. I did not get to them all today. I call upon you to do read some of the ones I did not mention.

As mentioned on the front page, teaching can be a wonderful and frightening act. It can help people enrich their lives, better themselves, and broaden the scope of their humanity. It can also be a means of destroying a way of thinking, for repressing a culture or ideas and it can used subjugate an entire group of people.

Before I go further, I would like to state that I’m assuming the readers of this blog have a general understanding of Residential Schools and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. For those that would like more information, please check out the following two links for more information.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

National Center for Truth and Reconciliation

If we are address the dangers of teaching it would be beneficial to look at it from the perspective e of those that have been done by harm by. I would argue that, for the most part, non-native children here in Canada have a rather positive or at least benign experience with school. By seeing it through the eyes of those that suffered because of others’ teaching practice we may have a better appreciation of how to be better teachers by being more aware of potential negative consequences.

The truth and reconciliation commission published a list of 94 Calls to Action in 2015 based on thousands of testimonies and affidavits presented by survivors and children survivors of residential schools.

It begins by stating:

“In order to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission makes the following calls to action.”

The 94 calls to action are a vital document that Canadians should be at least familiar with, if not have read in some capacity.

For the sake of this Entry I will focus on the ones that pertain to the nature of teaching and education. I won’t talk about all of them at great length but I will try to do justice to the ones I mention.

- We call upon all levels of government to fully implement Jordan’s Principle.

Named for Jordan River Anderson, this call to action states that when there is a dispute about jurisdiction and obligation of payment for services for status children, the point of first contact is to pay and to have disputes settled later. This is to avoid unnecessary delays that might lead to the harm of a child, student or patient.

- We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to develop culturally appropriate parenting programs for Aboriginal families.

In our course we talk a lot about teaching as transmission of knowledge but what if the knowledge that was to be transmitted was lost due to a program of deliberate destruction?

- We call upon the Government of Canada to repeal Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

The SPANKING law. The law, basically protects teachers, parents or others acting in such authority from criminal prosecution for using force upon a child. Considering what FNMI students went through, in terms of abuse, this call for a repeal is quite understandable.

The following calls to action are related to the funding of education to address reconciliation. This is an area where I need to do more research so for now, I encourage you to read them and become familiar with them. As time, and my blog progresses I hope to have greater insights in to this area.

- We call upon the federal government to eliminate the discrepancy in federal education funding for First Nations children being educated on reserves and those First Nations children being educated off reserves.

- We call upon the federal government to prepare and publish annual reports comparing funding for the education of First Nations children on and off reserves, as well as educational and income attainments of Aboriginal peoples in Canada compared with nonAboriginal people.

- We call on the federal government to draft new Aboriginal education legislation with the full participation and informed consent of Aboriginal peoples. The new legislation would include a commitment to sufficient funding and would incorporate the following principles:

- Providing sufficient funding to close identified educational achievement gaps within one generation.

- Improving education attainment levels and success rates.

iii. Developing culturally appropriate curricula.

- Protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, including the teaching of Aboriginal languages as credit courses.

- Enabling parental and community responsibility, control, and accountability, similar to what parents enjoy in public school systems.

- Enabling parents to fully participate in the education of their children.

vii. Respecting and honouring Treaty relationships.

- We call upon the federal government to provide adequate funding to end the backlog of First Nations students seeking a post-secondary education.

This is one of those fun ones for me because I have SO many people in my life that say things like, “gah, these indians get free university, why can’t they be successful.” This is the Disneyfied© version of what I’ve heard. I have little doubt that you’ve heard worse or have thought something similar. This sentiment is one of those warped misconceptions that only proliferates racism and hatred. FNMI people don’t get “free university.” They need to apply for funding from their band like most other students apply for scholarships. If the band has no funds or chooses to place their money into other programs then those students may be out of luck. (Murray, 2012)

- We call upon the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, in consultation and collaboration with Survivors, Aboriginal peoples, and educators, to:

- Make age-appropriate curriculum on residential schools, Treaties, and Aboriginal peoples’ historical and contemporary contributions to Canada a mandatory education requirement for Kindergarten to Grade Twelve students.

Age-appropriate here is the key. I’ve heard many teachers say that the subject is too hard to discuss with young children. But how young is too young? We are not talking about being graphic here or sexual education. Kindergarten? Perhaps too young? Grade 6… to late?

- Provide the necessary funding to post-secondary institutions to educate teachers on how to integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms.

This should also include school boards, not just post-secondary institutions, in my humble opinion.

iii. Provide the necessary funding to Aboriginal schools to utilize Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods in classrooms.

- Establish senior-level positions in government at the assistant deputy minister level or higher dedicated to Aboriginal content in education.

- We call upon the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Aboriginal education issues, including:

- Developing and implementing Kindergarten to Grade Twelve curriculum and learning resources on Aboriginal peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools.

- Sharing information and best practices on teaching curriculum related to residential schools and Aboriginal history.

iii. Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect.

- Identifying teacher-training needs relating to the above.

Of all the calls to actions, this one, 63, speaks to me most in terms of impact and immediacy. Most likely because I am a teacher. If there is any way for me to enact or help bring about change and reconciliation, it is through this particular Call to Action.

There are others, such as creating Early Childhood Education programs, offering degrees in aboriginal languages (12 and 16 respectively) and many others. I did not get to them all today. I call upon you to do read some of the ones I did not mention.

Works Cited

Murry, J (2012, Jan 15). True or False – Do Aboriginal People Get Free Post-Secondary Education? retreived from: http://www.netnewsledger.com/2012/01/15/true-or-false-do-aboriginal-people-get-free-post-secondary-education/ https://librarianship.ca/news/cbc-unreserved-trc-visuals/